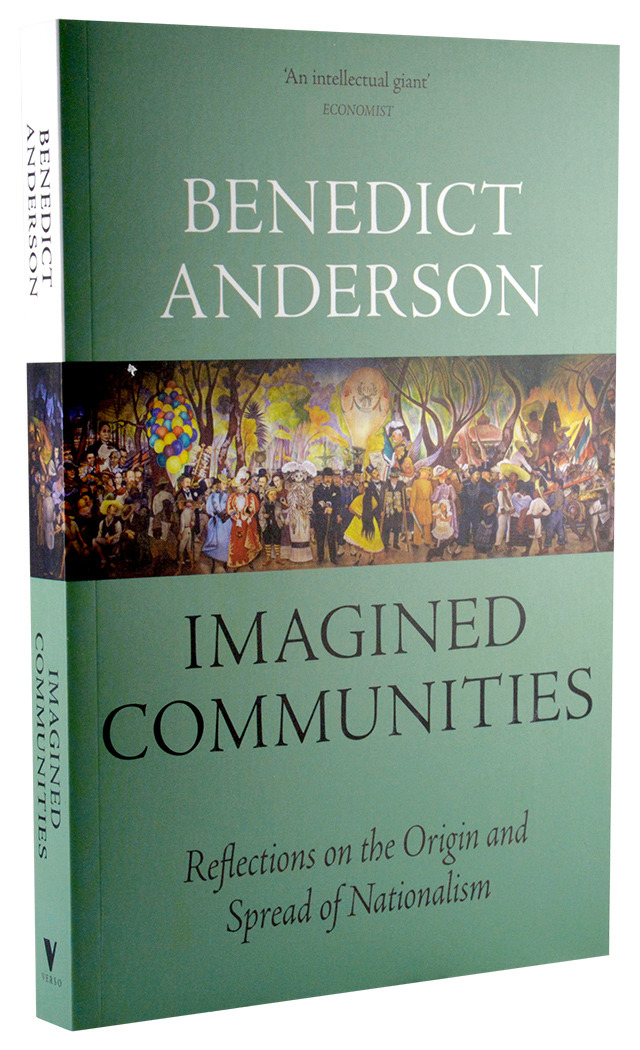

For Anderson, this last change is largely due to the technological innovation of the printing press, which enabled the wide dissemination of newspapers and novels.Īnderson expands upon this idea in the following chapter, “The Origins of National Consciousness.” Here, he argues that the convergence of capitalism, printing, and the diversity of vernacular languages led to the birth of national consciousness. This involved several historical shifts: the weakening of the medieval worldview and the religiously-based communities of Europe, the demotion of Latin as a sacred and administrative language in favor of vernaculars, the decline of dynastic monarchies, and the emergence of a new, secularized conception of time. Anderson then analyzes the cultural roots that enabled the birth of national consciousness in the modern era. He defines a nation as an “imagined political community” that is limited and sovereign, in which members feel a “horizontal” comradeship with each other. In the Introduction, Anderson addresses the paradoxical qualities of nationalism that complicate its theorizing. An afterword, in which Anderson reflects on the history of the book’s reception, was appended to the 2006 release.

Two chapters of supplementary material were added to the second edition, which appeared in 1991. The original edition of the book is divided into nine chapters, which analyze the cultural roots of the idea of the nation and provide a historical account of its political realization across the globe.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)